Cloud Hands - Yun shou

Compiled and Indexed by

Michael P. Garofalo, M.S.

Notes Links Bibliography Quotes Charts 8 Gates 5 Steps

Yang Style Taijiquan Chen Style Taijiquan

Index to the Thirteen Gates of

Taijiquan:

13 T'ai Chi Ch'uan Postures (Gates, Stances, Movements,

Techniques, Kinetic Movements, Tactics or Powers)

3. Press - Ji

4. Push - An

6. Split - Lieh

7. Elbow - Chou

11. Stepping to the Left Side - Ku

12. Stepping to the Right Side - Pan

13. Settling at the Center - Ding

General Remarks

The Thirteeen Postures (8 Gates and 5 Steps) are referred to in various ways by T'ai Chi Ch'uan authors. Some call them the "Thirteen Powers = Shi San Shi." Others call them the Thirteen Postures, the Thirteen Skills, the Thirteen Entrances, the Thirteen Movements, or the Thirteen Energies.

There are many references to the 13 Postures in the writings and teaching in both the Yang and Chen style of T'ai Chi Ch'uan that I have studied. Quotations Charts

The first Eight Gates or Eight Entrances (Ba Gua or Pa Kau) can be divided into the Four Primary Hands (Ward Off, Pull Back, Press and Push) and the Four Corner Hands (Pull Down, Split, Elbow and Shoulder).

The first eight (Pua Qua or Ba Gua) of the Thirteen Gates are often associated, for mnenomic or esoteric purposes, with the eight basic trigrams used in the Chinese I Ching: Book of Changes. In the order of the first Eight Gates (Pa-Men), the eight I Ching trigrams are Heaven, Earth, Water, Fire, Wind, Thunder, Lake, and Mountain. Quotations Charts

All thirteen postures, or course, involve some movement of the feet and legs, but the final Five Gates involve more extensive movements of the feet and legs. These are collectively referred to as the Wu-hsing - Five Elemental Phases of Change. The final five gates are associated with the 5 elementary processes (Wu-xing) involving: metal, wood, water, fire, and earth. Quotations Charts

This webpage work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License,

© 2004-2021 CCA 4.0

Eight Gates

(Eight Stances, Postures, Energies, Kinetic Movements, Ways)

1. Péng (掤)

Péng Jing is outward expanding and moving energy. It is a quality of responding to incoming energy by adhering to that energy, maintaining one's own posture, and bouncing the incoming energy back like a large inflated rubber ball. You don't really respond to force with your own muscular force (Li) to repel, block, or ward off the attack. Peng is a response of the whole body, the whole posture, unified in one's center, grounded, and capable of gathering and then giving back the opponent's energy.

Péng Jing is often referred to as a kind of "bouncing" energy. Péng Jing is also considered one fundamental way of delivering energy and embodied in some way in each of the other Eight Gates. Although, there are frequent references to "energies" or "intrinsic energies," Jing is more of a skill, an expertise developed through much practice, an experience, a pragmatic achievement. Authors such as Chen Kung identified 38 different intrinsic energies, e.g., Sticking/Adhering Jing, Listening Jing, Receiving Jing, Neutralizing Jing, etc. Jing is used in various ways in both offensive and defensive applications.

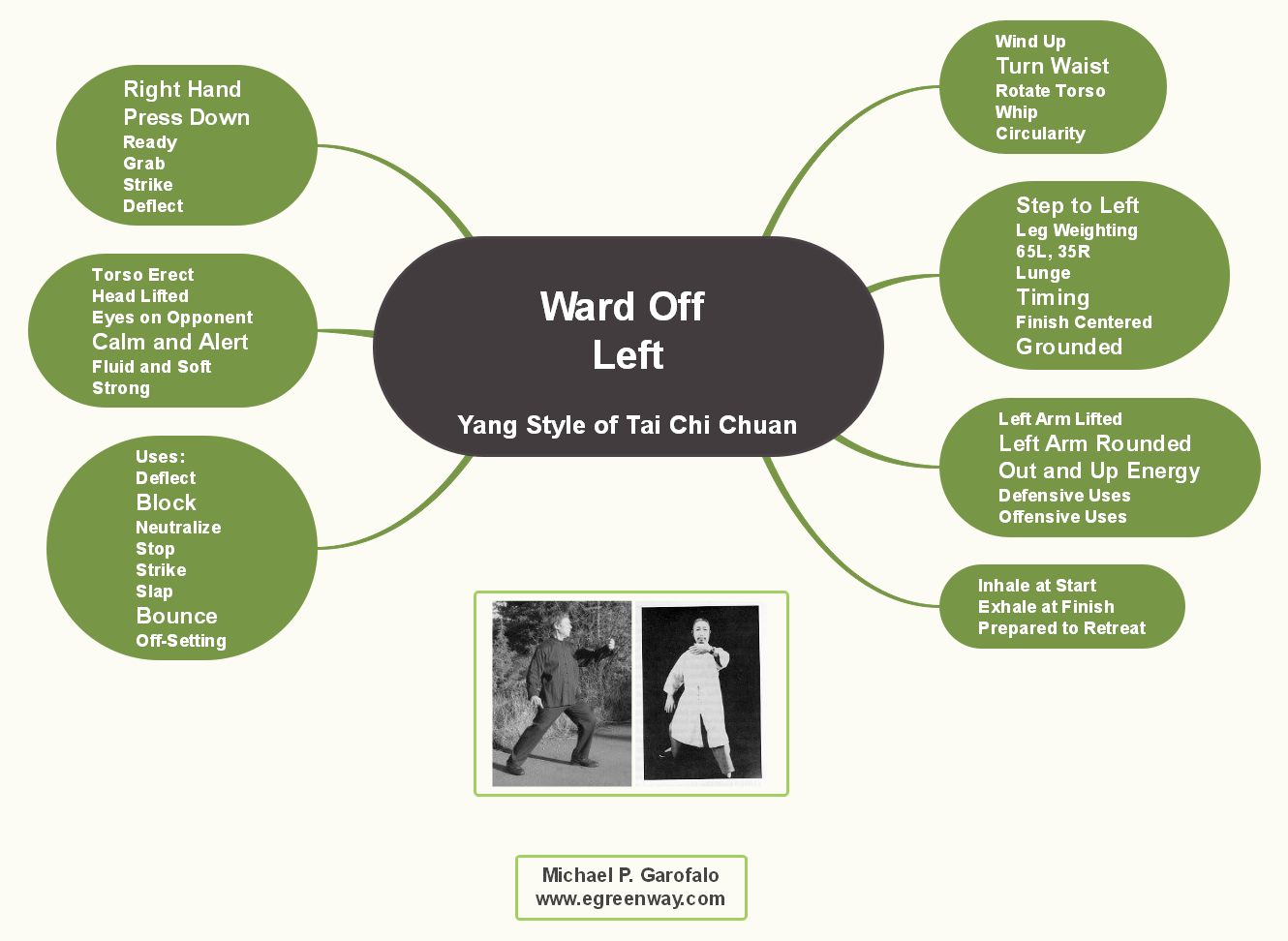

Examples of movements with Péng Jing Ward Off characteristics (i.e.,

stepping, turning waist, curved arm, outward and upward, strong lunge stance) in

the Yang 108 Taijiquan Form: Grasping the Sparrow's Tail (Ward Off Right),

Ward Off Left, Fair Lady Works the Shuttles, Press, Parting the Wild Horses

Mane.

"Peng Ching is the source of these eight methods.

When you Push Hands or practice the set, at no time can you neglect this

category of energy. Actually, one can say that T'ai Chi boxing is Peng

ching boxing because without Peng ching there is no T'ai Chi boxing. Peng

ching is the power of resilience and flexibility. It is born in the thighs

and called Ch'i kung. Ch'i kung is concealed through-out the entire body.

Then the body becomes the wheel's rubber band and you can gain achievement of

defense. But this is not the striking aspect. When you have this

reaction force, you then have the ability to strike by returning the strike to

its originator. This is the energy of the defensive attack. It is

used to evade and also to adhere. When moving, receiving, collecting, and

striking, Peng ching is always used. It is not easy to complete

consecutive movements and string them together without flexibility. Peng

ching is Tai Chi boxing's essential energy. The body becomes like a

spring: when pressed it recoils immediately."

- Kuo Lien-Ying, the T'ai Chi Boxing Chronicle, 1994, p.44.

"Taijiquan has been called Peng Jin Quan or "Peng Energy

Boxing" as described in the famous Chen book by Gu Liuxin and Chen Jiazheng.

Peng carries two meanings. The first is a sense of buoyancy throughout the

body, giving it a feeling of vitality and resilience (ne qi). It is

contained in every movement at all times and is an inflated, outward-expanding

energy. The second is an action, a technique that uses a vertical circular

movement that spirals upwards and outwards, intercepting and warding off an

advancing force. Peng energy is created by the elastic force of muscles,

combined with the elongation of the joints and tendons. It can be compared

with the buoyancy of water. On it a tiny leaf can drift, but it can also

carry a ten-thousand ton ship. Peng energy prevents and opponent from

reaching one's body. The Peng strength used never exceeds the strength an

opponent is using in attack. It is sufficient to hold off an attack, but

not to resist or stop the attack. The main purpose is to prevent the

opponent from reaching one's body and then to change the direction of the attack

by utilizing one of the other hand methods. Peng energy, therefore, acts

as the foundation for the change of energies in Push Hands. As it is an

organic (living) force, it can only be truly felt and realized in Push Hands.

It is difficult for those who have never pushed hands to fully comprehend this

concept. Proper understanding of the concept and acquisition of the

authentic skill cannot be achieved by attempts at logic or theoretical guessing.

Only through diligent and consistent as well as intellignt practice can one

reach a level of proficiency. Example of Peng: Transition from Single Whip

to Buddha''s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar."

- Davidine Siaw-Voon Sim and David Gaffnery, Chen Style Taijiquan,

2002, p. 152. "The Eight Kinetic Movement of Taijiquan" (Ba Fa)

"Peng is a form of Jing that responds to incoming energy

by adhering or sticking to it, and then bouncing the incoming energy back like a

large inflated rubber ball. It is the primary Yang or “projecting” energy force

in Tai Chi, and can be equally defensive and offensive. Peng is expressed by the

entire body as a whole, unified in your center and grounded. When one standing

in the correct Peng posture, it is almost impossible to move them. The

first energy is Ward Off, expressed as you Step Forward into the left Bow

Stance, round the left arm forward and float the right hand to the hip.

Peng puts a curved barrier between you and your opponent; creating a buffer zone

that prevents the first shock of an incoming attack from penetrating your

defenses. This buffer zone also gives you the critical microsecond to avoid

being overwhelmed by an attack, giving you neurological space to to deflect,

absorb or counter an attack. Peng energy can be compared to the type of

force that causes wood to float on water or a balloon to inflate, or a garden

hose to fill with a torrent of water. It has a “bounce off” sensation, like the

feeling of rebounding off of a beach ball or Yoga ball. It is Peng that enables

the Tai Chi fighter to hit opponents and cause them, as the Chinese like to say,

“to fly away.” Imagine a young mother standing on a crowded beach pier,

searching frantically for her child. After a moment, she spots her toddler

climbing up the pier railing, some 60 feet above the ocean. As she rushing to

grab her child, anyone in her way would literally be “bounced away” by her

singularly-focused forward energy. This is Peng."

- Tai Chi

Transformation

Or, imagine a 300 pound defensive NFL lineman in his

stance as he waits for the ball to be snapped. He rises, does a Ward Off

Right, and bounces the 300 pound offensive lineman back and too the side enough

for the defensive end to slide though and sack the quarterback. Or,

imagine delivering a winding and swirling back fist to an opponent's ear.

Or, your elbow in Ward Off might hit the opponent's sternum and render them

breathless. The whole arm is used as a club or sturdy cane in Ward Off.

- Michael P. Garofalo

One exercise style I enjoy practicing at home, and often

in my Taijiquan classes (2000-2017), is straight line repetition drills.

For example, do Ward Off Left, then Ward Off Right, then Ward Off Left ...

alternating and repeating in a straight line direction till the end of the room,

then turn, and go back to the other side of the workout space doing alternating

Ward Off Left and Right. Those who have practiced

Hsing Yi drills

are familiar with this style of movement. I did this exercise style with

Brush Knee Right and Left, Kick Right and Left, Fair Lady Right and Left, etc.

This can get vigorous with more speed and/or explosive moves. Also, you

can do Ward of Right and Left to the four cardinal directions, as with Fair Lady

Works Her Shuttles to four sides."

- Michael P. Garofalo

Quotations Charts

Péng (掤) - Ward Off

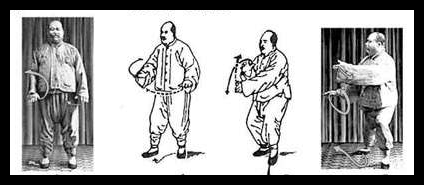

Ward Off Left by Yang Cheng Fu (1883-1936)

2. Roll Back - Lu

Roll Back - Lu

Lu Ching is receiving and collecting energy, or inward receiving energy.

Form movements: Grasping the Sparrow's Tail - Rollback

"Li is the use of force in a sideways direction, such as where we intercept and move with a forward directed attack, simultaneously diverting it slightly to one side and thus to the void. The greater the force of his attack, the greater the resulting loss of balance on the part of our opponent."

3. Press - Ji or C'hi

Press - C'hi, Qi or Ji

Chi or Ji Ching is pressing and receiving energy.

This is an offensive force delivered by following the opponent's energy, by

squeezing

of sticking forward.

Form movements: Grasping the Sparrow's Tail - palm pressing on forearm.

"What is the meaning of Pressing Energy? It functions in two ways:

(1) The simplest

is the direct method. Advance to meet (receive) the opponent, and then

adhere and

close in one action, just like in elbowing. (2) To apply reaction force is

the indirect

method. This is like a ball bouncing off a wall or a coin tossed onto a

drumhead,

rebounding off with a ringing sound."

- Stuart Alve Loson,

T'ai

Chi According to the I Ching, 2001, p. 73

4. Push - An

Push - An or On

An Ching is downward pushing energy.

Pushing power comes from the legs pushing into the earth.

Form movements: Grasping the Sparrow's Tail, Fair Lady Works the Loom.

Pushing or pressing with both palms in a downward direction, peng energy directed downward.

"What is the meaning of An energy?

When applied it is like flowing water.

The substantial is concealed in the insubstantial.

When the flow is swift it is difficult to resist.

Coming to a high place, it swells and fills the place up;

meeting a hollow it dives downward.

The waves rise and fall,

finding a hole they will surely surge in."

- T'ang Meng-hsien,

Song

of An

"What is absolutely

necessary in the beginning is to follow

the imagination. For instance:

when the two hands form the Push gesture, there is an imagined intent to the

front, as if an opponent was really there. At this time, within the plams of the

hands there is no

ch'i which can be issued. The practitioner must then imagine the ch'i

rising up from the

tan-tien into the spine, through the arms and into the wrists and palms.

Thus, accordingly,

the ch'i is imagined to have penetrated outwards onto the opponent's body."

-

Chen Yen-lin, 1932, Cultivating the Ch'i, Translated by Stuart Alve

Olson, 1993

"An Examination of T'ai Chi Push Methods." By Hiu chee Fatt. T'ai Chi: The International Magazine of T'ai Chi Ch'uan. Vol. 27, No. 2, April 2003, pp. 21-25.

"Arn: This posture is normally called to push. However this is also

incorrect as it means to 'press'. This is again a yang attacking movement coming from the whole

body issuing yin and yang Qi into the attacker's vital points on his chest. Many make

the mistake of looking after their legs when they hear about not being 'double weighted' but

neglect their hands. Never in Taijiquan is there a two-handed strike or attack using the

same power in each hand at the same time. There is a 'fa-jing' shake of the waist causing

one hand to strike just before the other. The hands are firstly yin, then yang thus

releasing yang Qi into the attacker."

- Earle Montaigue,

Tai

Chi 13 Postures, 1998

Push Hands: Links, Bibliography, Quotes, Notes.

5. Pull Down - Tsai

Pull Down - Tsai or Cai

Tsai Ching is grabbing energy.

A force delivered by a quick grab and pull, usually of an opponent's

writst, both backward and down.

Form movements: Needle at Sea Bottom.

"Tsai: Sometimes called 'inch energy'. Like picking fruit off a

tree with a snap of the wrist. Often on hand will be placed right on top of the other wrist to

assist in the power of this jerking motion. It is not a pull of his wrist but rather a violent

jerking fa-jing movement that can knock him out by its violent action upon his head jerking backwards and

kinking his brain stem. Again, the power must come from the centre and not only

from the arms and hands, and a follow up attack is also necessary."

- Earle Montaigue,

Tai

Chi 13 Postures, 1998

"Tsoi is where our opponent loses control of his centre of gravity, and we

use a technique to disrupt his balance to such an extent that he is uprooted completely from his

position. It

is something like a strategically placed lever lifting a heavy rock."

-

Principles

of the Thirteen Tactics

6. Split - Lieh

Split - Lie or Lieh

Lieh Ching is striking energy that splits apart an opponent.

Form movements:

Parting the Wild Horses Mane

Slant Flying

Wild Stork Flashes Its Wings

"Song of Split:

How can we explain the energy of Split?

Revolving like a flywheel,

If something is throw against it,

It will be cast off a great distance.

Whirlpools appear in swift flowing streams,

And the curling waves are like spirals,

If a falling leaf lands on their surface,

In no time will it sink from sight."

- "Yang Family Manuscripts," Edited by Li Ying-ang

"T'ai-chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions,"

1983, p. 33

7. Elbow - Zhou

Elbow - Zhou or Chou

Chou Ching is elbow striking energy.

Turn and Chop with Fist

"What is the meaning of Elbowing Energy? The function is in the Five

Activities:

advancing, withdrawing, looking-left, gazing right, and fixed rooting. The

yin and yang

are distinguished according to the upper and lower, just like Pulling. The

substantial

and insubstantial are to be clearly discriminated. If its motion is

connected and unbroken,

nothing can oppose its strength. The chopping of the fist is extremely

fierce. After thoroughly understanding the Six Energies (adhering, sticking, neutralizing,

seizing,

enticing, and issuing), the functional use is unlimited."

- Stuart Alve Loson,

T'ai

Chi According to the I Ching, 2001, p. 74

8. Shoulder - Kao

Shoulder - Kao

Kao Ching is a full body strinking energy. The peng energy is mobilized throughout the entire body, and then the entire body is used as one unit and the force is delivered with the shoulder or back.

Football players are familiar with this use of energy.

"Often called 'Shoulder strike: This method is used as a

third line of defence and can be quite lethal used at the correct distance. The

power must again come from the centre using the power of the legs and waist

together. Shoulder can be used from the front or from the back depending upon

the type of attack the your are receiving. If for instance is it a pull down

where you right shoulder is being pulled to your right, then you would use the

front part of the shoulder. If however, the attack pulled you to your left and

there was no time to use the front part, you would turn right around so that the

scapular part of your right shoulder could then slam into his chest using

fa-jing."

- Earle Montague

This webpage work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License,

© 2004-2021 CCA 4.0

Five Steps

(5 Steps, Directions, Footwork Techniques, Movements)

- Wu Bu

Nimble, responsive, and coordinated footwork is essential to success in all styles of martial arts. Taijiquan requires precise footwork and legwork. The placement and movement of the legs and feet as they relate to the powerful and coordinated application of energy in Tai Chi stances and postures gets extra attention by Taijiquan teachers in form work, drills, and push hands.

"In Chinese martial arts, Bu is a general term referring to stance and

foot/leg work. If we keep in mind our general definition for the Shi San Shi or the 13 Powers, an ideal

translation for Wu Bu might be something like: “powers based on the five stages of footwork” or, “the

five implicit behaviors of the stance” or even (considering the interactive nature of the Wu Xing), “the

five innate powers and conditions arising from the natural cycle of stages within the stance”.

It is the inherent behaviors, strengths and stages that are the subject in the Wu Bu, not the shape or

position of the stance as such. The innate conditions for power in stance work. We are also referring to

the cyclical way in which these powers emerge and dissolve. Also, as importantly, we are speaking of

the natural constraints inherent in the legwork."

- Sam Masich,

Approaching

Core Principles.

"Wubu are the five footwork skills.

Wu means five. Bu means step. In fact it is more about Shenfa - body movement skills because footwork and body movement have a very tight

relationship. They should be combined together. It is said "the body follows steps to move and

steps follow the body to changed, Body movement and footwork skills cannot be forgotten. If any of these is

omitted, one does not need

to waste his time practicing any more." The body movement skills and

footwork skills are about how to move the body in fighting. Only when the body can move to the right position

(distance and angle), can the hand skills work well. Thus, it is said Wubu is the foundation of

Bafa."

- Break Step, an Entering Forward Step.

Five

Stepping Methods of Taijiquan

The association of various Kicks with the Five Stepping Movements (9th to 13th Gates) is

based solely upon

a kickboxing training regiment that I use while doing walking or running

exercises. The

associations are my own, and, to my knowledge, have no connection whatsover to traditional

stepping theory in internal boxing. Tai Chi Chuan does use front heel

kicks, toe kicks, jump kicks, sweeping kicks, and knee strikes. The Five Stepping Movements (i.e., forward, backward, to the left, to the right,

and staying in place) all primarily

involve movements

of the legs and feet, with little emphasis upon the arms or hands. When kicking, the

arms are used to balance the body, facilitate the control, power, or speed of

the kicks, and

to have the

arms in a defensive position. It seems to me appropriate to

associate kicking techniques with the Five Stepping Movements. In Tai Chi Chuan practice, kicking is done slowly,

effortlessly, gently, and smoothly; and considerable balance and strength are required to extend the legs fully,

slowly, and in strict form. In kick boxing practice the kicks are done with much more speed and power.

These are the Yin and Yang approaches to kicking; and, both approaches are needed by martial

artists.

9. Advancing Steps - Jin

Advancing Steps, Stances, and Looking (Jin Bu)

Brush Knee and Twist Step

Generally speaking, when moving forward, step forward with your heel

first. Carefully transfer weight to the

forward foot, while being prepared to retreat the step as needed.

Walking forward exercise #6.

" This step is one of the main stepping methods of Taijiquan. The front

foot is placed down on its heel, then as the body moves forward, the toes are placed. However, the weight does not

come any more forward than the middle of the foot. The thighs and knees are curved and collecting while the

rear thigh is less curved than the front. We never retreat in Taijiquan and we can do this because of this

stepping method. The rear foot controls the waist in yielding and throwing away the attacker’s strength. The

waist is controlled during this step by the rear foot. There is an old Taijiquan saying: "To enter is to be born

while to retreat is to die". So we never retreat, we rely upon the rear leg controlling the waist for our power and evasiveness

without moving backward."

- Break Step, an Entering Forward Step.

Five

Stepping Methods of Taijiquan

Consider the advance movements in heel kicks and toe kicks with the right or left leg.

Forward movement is associated with the Element Metal.

10. Retreating Steps - Tui

Retreating Steps, Stances, and Looking Back (Tui Bu)

Step Back and Repulse Monkey

Generally speaking, when moving backward, step backward with your toe

first. Carefully transfer weight to the

backward moving foot, while being prepared to return the foot

forward as needed.

Consider the turning backward set up for a back kick with either the right or left legs.

Backward movement is associated with the Element Wood.

11. Stepping to the Left Side After Faking Right - Ku

Left Side Moving Steps, Stances, after Gazing to the Right (You Pan) or

faking to the right.

Rolling on one foot

Parting the Wild Horse's Mane

Waving Hands Like Clouds

Strike the Tiger

Deflect, Parry and Punch

Single Whip

Toe kicks with the left leg.

Heel kicks with the left leg.

Sweeping kicks with the left leg.

Jumping kicks with the left leg.

Side kicks with the left leg

Spinning kicks with the left leg.

Movement to the left and looking to the left is associated with the Element Water.

12. Stepping to the Right Side after Faking Left - Pan

Right Side Moving Steps, Stances, after Looking to the Left (Zou Gu) or

faking left.

Rolling on one foot

Parting the Wild Horse's Mane

Strike the Tiger

Brush Knee and Twist Step

Slant Flying

Toe Kicks with the right leg

Heel Kicks with the right leg

Sweeping kicks with the right leg.

Jumping kicks with the right leg.

Side kicks with the right leg.

Spinning kicks with the right leg.

Movement to the right is associated with the Element Fire.

"Song of Look-Right:

Feigning to the left, we attack to the right

with perfect Steps.

Stricking left and attacking right,

we follow the opportunities.

We avoid the frontal and advance from the side,

seizing changing conditions.

Left and right, full and empty,

our technique must be faultless."

- "Yang Family Manuscripts," Edited by Li Ying-ang

"T'ai-chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions,"

1983, p. 37

"Gu (or Zuogu - left look around) means to go forward sideways; that really

means to close up to the opponent indirectly. Here Zuo (left) means sideway; Gu (look around) means look

after or being careful. Usually in martial arts this term means defensiveness within attacking skills. So the main idea of

Zuogu is how to rotate and advance forward from sideway with some defense skills. It is usually called rotate

attack. It is wood which means straight and grow up continually. It belongs to Ganjin (Liver Channel). When the

key point Jiaji is focused on, the qi will automatically urge the body to rotate and advance forward."

- Zhang Yun,

Tai

Chi 13 Postures (This webpage offers some depth of interpretation

about the 13 Postures.)

13. Settling at the Center - Ding

Settling at the Center, Rooting Stances, and Holding Still - Zhong Ding

Golden Cock Stands on Right Leg - Left Knee

Strike

Golden Cock Stands on Left Leg - Right Knee Strike

Needle at Sea Bottom

Fair Lady Works the Shuttles

Centering, holding to one's center, maintaining equilibrium, settling, moving downward, and staying balanced at one's center are associated with the Element Earth.

Knee strikes with the right or left knee.

Links and Resources about the Thirteen

Gates of T'ai Chi Ch'uan:

12 Taijiquan Postures (Movements, Stances, Techniques, Energies or Powers)

Links and Bibliography

Chang San-Feng, Zhang Sangfeng History, Legends,

Bibliography, Lessons, Resources, Quotations, Notes, Links. Research by

Mike Garofalo.

Chen Style of Taijiquan "The Old Frame Chen Style of Tai

Chi bears a close resemblance to the New Frame Chen Style and also to the Zhao Bao and Hu Lei styles.

Apparently it is not based on

the classic '13 postures' which are central to the Yang and Wu Styles of Tai Chi." "Chen Fa Ke had replied that his art was

not

based on the 13 postures."

Chen Taijiquan

Bibliography, Lessons, Lists, Resources, Quotations, Notes, Links.

Research by Mike Garofalo.

Cheng Man-Ch'ing (1901-1975)

Chen

Style Taijiquan: The Source of Taiji Boxing. By Davidine

Siaw-Voon Sim and David Gaffney. Berkeley, CA, North Atlantic Books, 2002.

Index, charts, 224 pages.

"Clarifying the Meaning of Peng Energy." By Hiu Chee

Fatt. T'ai Chi, April, 2002, Volume 26, No. 2, pp. 44-47.

The

Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan: A Comprehensive Guide to the Principles

and Practice. By Wong, Kiew Kit. Shaftesbury, Dorset, Element,

1996. Index,

bibliography, 316 pages. ISBN: 1852307927. The Thirteen Gates are

described

and analyzed on pages 40 - 63: Fundamental Hand Movements and Footwork.

Combat sequences

and tactics using the Eight Gates are found on pages 100 - 150.

Cultivating the Civil and Mastering the Martial: The Yin and Yang of Taijiquan.

By Andrew Townsend. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, no

publisher listed on titlepages, 2016. No index, brief bibliography, 424 pages.

Small typefont. This volume is a huge compendia of information,

comprehensive in scope, with good explanations, observations, insights, and

summaries, etc.. This thick book includes some precise and detailed

movement descriptions, sound Taijiquan teaching on many topics, and more than

five hundred photographs and illustrations. A heavy reference volume for

your desktop; ebook versions for your tablet or phone or Kindle. ISBN: 978-1523258536. VSCL. "Andrew Townsend has

been practicing martial arts for more than forty years and began practicing taijiquan in 1990. Mr. Townsend is a certified taijiquan instructor and a

senior student of Grandmaster Jesse Tsao. He is a retired college

professor and has been actively teaching taijiquan for the past ten years.

He lives and teaches in Ormond Beach, Florida."

Eight Section Brocade Chi Kung Bibliography,

Resources, Quotations, Notes, Links. Research by Mike Garofalo.

The

Essence of T'ai Chi Ch'uan: The Literary Tradition. Translated and

edited by

Benjamin Pang Jeng Lo; Martin Inn, Robert Amacker, and Susan Foe.

Berkeley,

California, North Atlantic Books, 1985. 100 pages. ISBN:

0913028630.

Includes translations of works on the Thirteen Postures (pp. 41 -

66).

Expositions of

Insights Into the Practice of the Thirteen Postures. By Wu,

Yu-hsiang. Paraphrased by Lee N. Scheele.

Five

Steps: Meditative Sensation Walking. By Paul Crompton. Midpoint

Trade Books,

1999. 80 pages. ISBN: 187425060X.

The

Intrinsic Energies of T'ai Chi Ch'uan. Compiled and translated by

Stuart Alve Olson. Chen Kung Series, Volume Two. Saint Paul, Minnesota, Dragon Door

Publications, 1994.

Index, 194 pages. ISBN: 093804513X.

Meditation: Links,

Bibliography, Notes, Quotes.

Compiled by Mike Garofalo.

Principles

of the Thirteen Tactics

Push Hands (T'ui Shou): Bibliography,

Resources, Quotations, Notes, Links. Research by Mike Garofalo.

Relaxation, Fangsong, Sung:

Bibliography, Resources, Quotations, Notes, Links. Research by Mike

Garofalo.

Silk Reeling

(Chan Ssu Jin): Links, bibliography, quotes, notes.

Song of the Thirteen

Postures. Paraphrased by Lee N. Scheele.

Song of

13 Postures. By Dennis Watts, Gold Coast Tai Chi Academy,

Australia.

Song of the

Thirteen Postures. Translated by Benjamin Pang Jeng

Lo.

Sun Lu Tang's Style of Taijiquan

Songs of the Eight Postures. Attributed to T'an,

Meng-hsien. As researched by Lee N. Scheele.

T'ai

Chi According to the I Ching: Embodying the Principles of the Book of Changes.

By Stuart Alve Olson. Rochester, Vermont, Inner Traditions International

Ltd., 2001. 224 pages. ISBN: 0892819448. This book provides a

detailed and well researched

analysis of how the I Ching Trigrams are related to various Tai Chi

postures/movements,

using the Yang form as the basis for associations.

The

T'ai Chi Boxing Chronicle. Complied and explained by Kuo,

Lien-Ying. Translated by Guttmann. Berkeley, California, North Atlantic Books, 1994.

141 pages. ISBN: 1556431775. The Eight Gates and Five Steps are explained on pages

43 -60.

T'ai

Chi Chuan: The Martial Side. By Michael Babin. Boulder,

Colorado, Paladin Press,

1992. 142 pages. ISBN: 0873646797. Thirteen postures on pages 83 - 98.

T'ai

Chi Classics. By Waysun Liao. New translations of three

essential texts of T'ai Chi Ch'uan with commentary and practical instruction by Waysun Liao.

Illustrated by the author. Boston, Shambhala, 1990. 210 pages. ISBN: 087773531X.

Tai Chi

Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Translation, commentary

and editing by Douglas Wile. Sweet Chi Press, 8th Edition, 1983. 159

pages.

ISBN: 091205901X.

Taijiquan Links and Bibliography

Taiji Thirteen

Postures, Master Shouyu Liang

The Tao

of T'ai-Chi Ch'uan: Way to Rejuvenation. By Jou, Tsung, Hwa.

Edited by Shoshana

Shapiro. Warwick, New York, Tai Chi Foundation, 1980. 263 pages.

First Edition. ISBN: 0804813574. The Eight Gates are described and explained on pages

226-239.

Taoism and Tai Chi Chuan

By James Leporati.

Thirteen Animals

of Taijiquan "1. Dragon: Playing 2.

Tiger: Pouncing 3. Snake: Coiling 4. Horse: Parting 5. Phoenix: Looking 6. Monkey:

Stretching 7. Bear: Walking

8. Toad: Gazing 9. Chicken: Fighting 10. Magpie:

Jumping 11. Crane: Dancing 12. Lion: Turning 13. Lynx: Catching."

The Thirteen Gates of T'ai Chi Ch'uan: Notes,

Bibliography, Links and Quotations.

By Michael P. Garofalo.

Thirteen Postures

Yangjia Michuan Taijiquan

Thirteen Tai Chi

Postures by Earle Montaigue

13 Postures of Taiji.

By Mike Sigman. Article in 'Internal Martial Arts": October,

1999.

Note the differences between the Chen and Yang styles for the 5 steps. The

Chen

style: "Teng: Sudden upward-angles strike (Yang: step forward), Shan:

Sudden emptying

downward (retreat back); Zhe: Bend/close opponents arm back on him (look left);

Kong:

Sudden empytying not quite downward (Gaze Right); and Huo: Overall smooth

and flowing (central equilibrium)."

"Wang Haijun on Eight

Methods of Training Jin," by David Gaffney, T'ai Chi: The

International Magazine of T'ai Chi Ch'uan: Vol. 29, No. 4, August, 2005, pp. 5-10.

Translation by Davidine Diaw-Voon Sim.

Yang Style of Taijiquan. Bibliography, Resources, Quotations, Notes,

Links. Research by Mike Garofalo.

Yang Family Tai Chi Chuan,

Training Basics, Part 1. Includes drills for practicing

the Eight Gates. Videotape features Master Lu, Gui Rong.

65 minute videotape.

Yang Family Style Tai Chi Chuan Traditional Long Form,

108

Movements. By Michael P. Garofalo. Provides a list of the movements divided into five sections for teaching (.html and .pdf versions available).

Includes a bibliography, links, notes, and quotations. Provides a list comparing the Yang

Long Form

108 to 85 postures sequence.

Section 1, Movements 1-17, 48 Kb, PDF Format

Section 2, Part I, Movements 18-37, 54 Kb, PDF Format

Section 2, Part II, Movements 38-55, 49 Kb, PDF Format

Section 3, Part I, Movements 56-82, 64 Kb, PDF Format

Section 3, Part II, Movements 83-106, 63 Kb, PDF Format

Yang Style Tai Chi Chuan Short Form, Peking Version 24 Movements.

Lessons, Lists, Bibliography, Resources, Quotations, Notes, Links.

Research by Mike Garofalo.

This webpage work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License,

© 204-2021 CCA 4.0

Quotations about the Thirteen Gates of

T'ai Chi Ch'uan:

13 Taijiquan Postures (Movements, Techniques, Stances, Energies or Powers)

Quotations

"In the Long Form, Ward Off, Rollback, Press, Push, Roll-Pull, Split,

Elbow, and Lean Forward are called the

forms of the Eight Diagram (Pakua), the movement encompassing the eight directions. In stance, moving

forward, backward, to the right side, to the left side, and staying in the

center are called the Five-Style Steps. Ward Off, Rollback, Press, and Push are called the four cardinal

directions. Roll-Pull, Split, Elbow, and Lean

Forward forms are called the four diagonals. Forward, backward, to the

left side, to the right side, and center

are called

metal, wood, water, fire and earth, respectively. When

combined, these forms are called the thirteen

original styles of T'ai Chi Ch'uan."

- Master Chang San-Feng, from a text dated circa 1600 CE, "T'ai Chi Classics," Translated

by Waysun Liao, p. 95

"The Shi San Shi or ‘Thirteen Powers’ are universally

regarded as the energetic and conceptual core of Taijiquan training. They are

considered to be the source of all stylistic variations of Tai Chi and the

universal key which unlocks the secret of all Taijiquan. It is said that without

Shi San Shi

at the root, one’s art cannot be called Taijiquan. The Shi

San Shi consist of thirteen specific power qualities used in martial arts.

These are broken into two main categories, the first of which contains eight

components associated with the structure and operation arms and hands. These are

called Peng, Lü, Ji, An and Cai, Lie, Zhou, Kao (Ward-off, Roll-back,

Press, Push

and Pull-down, Split, Elbow, Shoulder). The second category contains

five components which relate to the structure and operation of the legs and

feet. These are called Jin Bu, Tui Bu, Zou Gu, You Pan and Zhong Ding

(Advance Step, Retreat Step, Left-side Gazing, Right-side Looking and Central Settling). The theory is not fanciful. It supports a reasoned and practical

methodology for adroitly managing the dynamics of interaction within a specific

range of hand combat."

- Sam Masich,

Shi San Shi: The

Thirteen Powers

"The taiji form is therefore, a set of postures designed

to express the taiji principles. Indeed, the oldest masters of taiji did not practice a "taiji form." They took basic

postures from martial arts and health-exercise forms and infused them with specific (taiji) principles. These basic postures

are

known as: the 5 steps and the 8 gates.

Together they are called the core "13 postures of taijiquan."

Practiced in an impromptu way, these basic moves were put together in various combinations that flowed into one another.

This was the original way of taijiquan."

- Alpha Holistics,

Learning

Tai Chi Chuan

"In tai chi practice, each

of the five elements is represented by the five lower body directions: forward=metal, backward=wood, look left=water, gaze right=fire, and central equilibrium=earth. The five elements combine with the eight trigrams to create the 13 postures of t'ai chi chuan. The

eight trigrams (the eight gates) define

the eight energies in t'ai chi: peng, lu, ji, an, tsi, jou, kou, lie. The

thirteen postures form the basis for all techniques in tai chi."

- Sifu Bob Marks,

Five Elements Theory,

Five Elements Tai Chi Chuan School

"Kuo, Lien-Ying's chronicle on Tai Chi makes clear that no matter what style

one practices all forms of Tai Chi

must conform to the classic qualities of the

art as they have been recorded throughout history. This means there is only one T'ai Chi Ch'uan. These qualities are referred to as the Ba-gua (8) gates and

Wu-hsing (Five Elemental Phases of Change) steps. Together they constitute Tai

Chi's 13 movements."

-

Notes

on Yang, Lu Chan

"The Eight Trigrams and Five Elements are a part of man's natural

endowment. We must

first understand the basis of work: conscious movement. Only after

grasping conscious

movement are we abel to interpret energy, and only after interpreting energy can

we reach

the level of spiritual insight. Thus the first stage of our work is

understanding conscious movement, which although it is a natural endowment is extremely

difficult for us

to acquire."

- Yang Ch'eng-fu, Self Defense Applications of T'ai-chi Ch'uan, 1931

Tai Chi

Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions, p. 133.

"Taiji Quan is often

called Taiji Shi San Shi (Taiji Thirteen Postures) or just Shi San

Shi. Thirteen

is the special number in Taiji Quan. Behind this number is the complete principle of

Taiji Quan. This principle is respected and followed by all generations of Taiji groups for more than two hundred years.

It is the foundation of Taiji Quan. Thus, to learn this principle is really important for Taiji Quan practice.

Without understanding it well, one cannot reach high level Taiji Quan skills. Shi San Shi - Thirteen

Postures does not mean thirteen different postures or movements. Actually

it

means thirteen basic skills; and moreover, it means thirteen basic attributes for advanced

study. They are the foundation of all Taiji Quan skills. It is said all other skills come from the different variation and

combination of these skills.

- Zhang Yun,

Taiji

Thirteen Postures

"You must pay attention to the turning transformations of empty and

full,

and the chi moving throughout your body without the slightest hindrance. In the midst of stillness one comes in contact with movement, moving as though remaining still. According with one's opponent, the transformations appear wondrous. For each and every posture, concentrate your mind and consider the meaning of

the applications. You will not get it without consciously expending a great deal of time and

effort. Moment by moment, keep the mind/heart on the waist. With the lower abdomen completely loosened, the chi will ascend on its own."

-

Song

of the Thirteen Postures

"Move the chi as though through a pearl carved with a zigzag path

(nine-bend pearl), reaching everywhere without a hitch. Mobilize energy that is like well-tempered steel capable of

breaking

through any stronghold. One's form is like a hawk seizing a rabbit. One's spirit is like a cat seizing a

rat. Be still like a mountain, move like a flowing river. Store energy as though drawing a bow. Issue energy (fa

jin) as though releasing an arrow. Seek the straight in the curved.

Store up, then issue. The strength issues from

the spine; the steps follow the body' changes. To gather in is in fact to release. To break off is to again

connect. In going to and fro there must be folding; in advancing and retreating there must be turning transitions. Arriving at the extreme of yielding softness, one afterward arrives at the extreme of solid hardness."

- Wu Yu Xiang,

Mental

Elucidation of the Thirteen Postures

"The apocryphal founder of Tai Chi was a monk of the Wu Tang Monastery,

Chang San-feng to whom have been ascribed various dates and longevity's. Some scholars doubt his historical

existance, viewing him as a literary construct on the lines of Lao Tzu. Other research and records from

the Ming-shih (the official chronicles of the Ming dynasty) seem to indicate that he lived in the period

from 1391 to 1459. Linking some of the older forms with the notion of yin-yang from Taoism and

stressing the 'internal' aspects of his exercises, he is credited with creating the fundamental 'Thirteen

Postures' of Tai Chi corresponding to the eight basic trigrams of the I Ching and the five elements."

- Christopher Majka,

The

History of Tai Chi

"The thirteen postures should not be taken lightly;

The source of the postures lies in the waist.

Be mindful of the insubstantial and substantial changes;

The ch'i (breath) spreads throughout without hindrance.

Being still, when attacked by the opponent, be tranquil and move in stillness;

Changes caused by the opponent fill him with wonder.

Study the function of each posture carefully and with deliberation;

To achieve the goal is very easy.

Pay attention to the waist at all times;

Completely relax the abdomen and the ch'i (breath) rises up.

When the coccyx is straight, the shen

(spirit) goes through the headtop.

To make the whole body light and agile suspend the headtop.

Carefully study."

-

The

Song of Thirteen Postures. Translated by Benjamin Pang Jeng Lo, Martin Inn, Robert Amacker and Susan Foe,

1985.

"Taijiquan is sometimes referred to as the shi san shi -

thirteen postures. This name is derived from the notion that there are thirteen

basic postures, energies or skills that run throughout the whole of taijiquan,

and all other skills come from variations and combinations of these skills.

The shi san shi are normally divided into two: Ba fa (eight methods) - these are

shou fa (hand skills) and Wu ba (five steps)- these are shen fa (body movement

skills). Although this tradition is primarily received through the Yang

tradition, the Chen tradition is somewhat different, there are a number of

similarities and it can be interesting to relate the shi san shi back to the

principles and traditions of Daoism, from which both families draw. The

shi san shi relates to two of the most important theoretical documents of taiji

and Daoism the Taiji T'u (Taiji Diagram) of Chen Tuan (although most people are

probably familiar with it through the Neo-Confucian re-interpretation of Chou

Tun'yi) and Fu Hsi's pre-heaven arrangement of the bagua derived from the Yellow

River diagram (again this diagram is perhaps best known through Shao Yung's

Hsien T'ien T'u. Ostensibly all of these two diagrams describe the same thing -

the passage from wuji (original nothingness) through to physical manifestation.

Chen Tuan and Chou Tun-yi describe the movement form wuji through yin and yang

and the five elements to manifestation, while Shao Yung applies the logic of the

Yijing to Fu Hsi's bagua arrangement and shows the process of manifestation from

wuji to taiji, the bagua and ultimately the hexagrams. For Chou Tun-yi the

five elements equate with taiji and underlie the manifestation of the bagua at

the same level as yin and yang. The mixing and changing of yin and yang within

taiji is the same as the dynamic relationships of creation and destruction

between the five elements. Thus the five elements underlie the bagua just as yin

and yang underlies the bagua."

-

Thirteen Postures from Absolute Tai Chi

- Mark Tinghei, "A

Synopsis of Taijiquan"

Thirteen Principles of T'ai Chi Ch'uan Practice:

"The enduring legacy of Taijiquan is that

qi grows by the practice methodology, as a plant by tending and watering.

Along the way, the qi nurtured in daily practice alleviates stress related

illnesses. In the longer term, the qi buildup invigorates and

strengthens the body's constitution, and serves as a natural preventive medicine

that shields against chronic ailments. The alluring promise is that the store

of qi preserves the "spring of life" in old age, as espoused in the verse

of the Song of Thirteen Postures.

Yi shou yan nian bu alo chun

One gains longevity and prolongs the spring of life in old age."

- C.P. Ong,

Taijiquan: Cultivating Inner Strength,

p. 156

"The last five of Taijiquan’s Shi San Shi,

or Thirteen Powers (oft. “Postures”) are the Wu Bu, usually translated as the five directions, the five steps, the five phases or

the five elements.

Although these are said to be fundamental aspects of Tai Chi training, it is

rare to find a Tai Chi practitioner with a truly integrated sense of the Wu Bu, and problems abound

with regard

to interpretation and the application of the Wu Bu theory. To complicate

the issue there is very little available material exploring this subject. Most books provide

at best a cursory explanation or a simple list"

- Sam Masich,

"Taiji Quan, the other name

is Chang Quan (Long Fist), also named Shi San Shi (Thirteen Postures). It is Chang Quan because it likes a long river and an ocean flowing forever wave by

wave. Shi San Shi is Peng, Lu, Ji, An, Cai, Lie, Zhou, Kao, Jin, Tui, Gu, Pan, Ding. Peng, Lu, Ji,

An, that is Kuan, Li, Zhen, Dui, are the four straight directions. Cai, Lie, Zhou, Kuo, that is Qian, Kun,

Gen, Xun, are the four diagonal directions. This is Bagua (Eight Trigrams). Jinbu, Tuibu, Zuogu,

Youpan, Zhongding, that is metal, wood, water, fire, earth, is Wuxing (Five Elements). To combine these

together is Shi San Shi."

- Wang Zongyue,

Tai Chi Classic,

"Explanation of the Name of Taiji Quan."

Sink, relax completely, and aim in one direction!

In the curve seek the straight, store, then release.

Be still as a mountain, move like a great river.

The upright body must be stable and comfortable

To be able to sustain an attack from any of the eight directions.

Walk like a cat.

Remember, when moving, there is no place that does not move.

When still, there is no place that is not still.

First seek extension, then contraction; then it can be fine and subtle.

It is said if the opponent does not move, then I do not move.

At the opponent's slightest move, I move first."

To withdraw is then to release, to release it is necessary to withdraw.

In discontinuity there is still continuity.

In advancing and returning there must be folding.

Going forward and back there must be changes.

The form is like that of a falcon about to seize a rabbit;

The shen is like that of a cat about to catch a rat.

- Wu Yuxian (1812-1880), "Expositions of Insights Into the

Practice

of the Thirteen Postures."

"All the thirteen postures of Tai Chi Ch’uan must not be treated lightly. The meaning of life originates at the waist.

When moving from substantial to insubstantial, one must take care that the Chi is circulated throughout the entire body with out the slightest hindrance.

Find the movement in the stillness, even stillness in movement. Even when you respond to the opponent’s movement, show the marvel of the technics and fill him with wonder.

Pay attention to every posture and study its purpose. That way you will gain the art without wasting your time and energy.

In every movement you must pay attention so as the heart (mind) stay on the waist, then completely relax the abdomen, and your Chi will rise up.

Your Tail Bone should be centered and upright so as your spirit (Shen) rises to the top of the head. The top of the head is suspended and the entire body is relaxed and light.

Carefully study and pay attention when doing research, extension and contraction, opening and closing follow their freedom.

To enter the door and to be led along the way, you need to have oral instruction; practice without ceasing, and the technic is achieved by self-study.

When asked about the standard, function and application of the thirteen postures, the answer should be the Yi (mind) and Chi are the master, and the bones and muscles are the chancellor.

Carefully investigate what the ultimate meaning is: to increase and extend our health and age, and maintain a youthful body.

The song consists of one hundred and forty characters,

every character is true and its meaning is complete. If you do not approach and

study in this manner, then you will waste your time and energy, and sigh in

regret."

-

Dennis Watts

"The Eight Trigrams and Five Elements are a part of man's natural

endowment. We must

first understand the basis of work: conscious movement. Only after

grasping conscious

movement are we abel to interpret energy, and only after interpreting energy can

we reach

the level of spiritual insight. Thus the first stage of our work is

understanding conscious

movment, which although it is a natural endowment is extremely difficulat for us

to acquire."

- Yang Ch'eng-fu, Self Defense Applications of T'ai-chi Ch'uan, 1931

Tai Chi

Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions, p. 133.

"The thirteen basic postures must never be regarded lightly. The original

source of their meaning is in the waist. In changing and turning from

substantial (Yang) to insubstantial (Yin) and vice versa, one must pay close

attention; ch'i will circulate throughout the entire body without the slightest

hindrance. Inwardly tranquil, one responds to a forceful action while

maintaining an unruffled attitude. Manifest your inscrutable techniques to

accord with an opponent's changing actions. Pay special attention to your

every posture and seek out its hidden meaning, then you can acquire this art

without exerting excessive effort. Pay attention to your waist at all

times. When the abdomen is completely relaxed, the ch'i will soar up (and

circulate through the entire body). When the lowest vertebrae are plumb

erect, the spirit of vitality reaches to the top of the head. When the top of

the head is held as if suspended from above, the whole body feels light and

agile. Examine and investigate carefully and thoroughly. Whether bending,

stretching, opening, or closing, let it take its natural way. To enter the

gate and be guided onto the correct path one requires verbal instruction from a

competent master. If one practices constantly and studies carefully, one's skill

will take care of itself. If one asks about the correct standard of

substance and function, (the answer is that) the mind and ch'i direct, and the

flesh and bones follow. Carefully examine what the ultimate purpose

is--the enhancement of longevity, rejuvenation, and immortality. The Song

of the T'ai Chi Thirteen Postures contains 140 Chinese words. Each one is

genuine and true doctrine which explains fully and without reservation the

meaning and purpose of T'ai Chi. If you do not seek carefully in the direction

indicated above, your time and effort will be spent in vain and you will have

cause to sigh with regret."

- Song of the Substance and

Function of the Thirteen Postures

"I believe the concept of "center" in Jiulong and

the Daoqiquan arts is broader than the concept of "center of gravity"

in mathematics/physics. In addition to your physical center of gravity,

the "centeredness" of your mind, your intent, and the

state of your Song are part of the equation as well. If fear causes you to

"rise up" to flee, then fear has raised your center. And that's

not necessarily bad, if your intent is to be light on your feet and run as fast

as you can."

- Stewart Warren,

Jiulong Baguazhong # 1360, 31 Jan 2006

"Before exploring the 8 jin, it is important to

understand that these explanation of Jin refer to three occurrences in

most cases:

1) an essential internal movement method of the practitioner relating to

specific shenfa (body methods particular to the system) of that Jin,

2) a strategic method of engagement to external action or force,

3) a variety of tangible application methods that can be named as "X" type of

Jin methods.

These are different facets of the meanings of these Jin, this difference should be noted as is can be a bit confusing. Besides this, the skills of the eight Jin (and all other methods in Chen Taijiquan) in application and strategy ideally must be acquired on three levels; high, medium and low.1) Peng Jin (pronounced in English as something like [p'hung]): Peng Jin is the mother of Taijiquan Jin because without it, nothing else works. All applications and manifestations of other Jin necessarily include the existence of Peng to occur. This power is most easily described in the example of a rubber ball filled with air. This ball has a somewhat flexible or resilient exterior though is anchored to a particular location (or even a mobile location) at its center in the case of taijiquan by its frame illustrated in the legs' connection to the earth. Peng Jin, like a rubber ball, has a resilient and only slightly yielding exterior that naturally rolls when pressed in any location. Resilience in response to outward pressure and neutral rolling in any direction are its actions.

Peng as an isolated principle is Neutral, (non aggressive, non yeilding). Its consistent intent is to maintains its integrity as a resilient roundness with no attachment except to its anchor; Peng is not spatially nor structurally yeilding, in those facets it is neutral, yet it is directionally unfixed and yeilding.

In terms of actual applicable methods, Peng may show as upward or outward rolling. In action it is not necessarily neutral as it, like all the other JIN does not manifest in action in any isolated way, but only exists as compound methods.

2) LU JIN (pronounced something like [leeu]

Lu jin, like all other jin has peng as its foundation, but can be said to be more active and less neutral. Lu can be well described in the action of a swinging door, this one swings all kinds of ways and there is nothing but an empty hole behind it with probably a bunch of awkward unsafe objects to stumble over.

While Peng maintains integrity and rolls incoming force around it, Lu, on the other hand gets out of the way of force, disappears. This is the commonly referred to "leading to emptiness" in Tai Chi. Lu is not neutral, it is receptive, inviting. It manifests in practical action as "yeilding" to incoming force, though can even exist as a certain type of pulling.

3) JI JIN (pronounced [jee])

Ji jin means crowding power. It is not neutral in any way, it can be said to be the outwardly aggressive direct mutation of peng jin. We can say that this crowding power is the deliberate attempt to compress an opponents Peng jin or spatial/structural integrity. This basically means an effort to pop or flatten the opponents rubber ball.

Ji jin relies in diagonal method or "crossing". For example; if one is facing a the outside of a square two dimensionally, to collapse it is best acheived by folding it to a parallelogram. Practically one way this shows up is as crossing any of the opponents actions over his/her own center and compressing them. In essence it is just pure crowding (compression) of the opponent's structure.

4) AN JIN (pronounced something like[ahn])

An, is often said to refer to downward pressing, which is not inaccurate, yet it is a bit deeper than that.. An is like pressure, or pushing that is powered by weight. In useage this weight power may show up as (but is not limited to) the ability to move an opponent by placing the hands lightly on them without any visible pushing, as the weight or mass of the body is being employed as the power.

AN JIN is basically heaviness. This is to say that it may feel heavy to the opponent, and that it's potential derives from the skillful harnessing of the practitioners own mass. This JIN often appears passive as it show up simply as a reconfiguration of the practitioners current structure. AN appears when the practitioner wants to affect their mass=weight to the opponent via their structure, or simply make advantageous use of gravity.

- Martin Spivac, 8 Energies (Ba Jin) of Taijiquan

"Tai Chi Chuan is based on this theory, and therefore it is smooth, continuous, and round. When it is necessary to be soft, the art is soft, and when it is necessary to be hard, the art can be hard enough to defeat any opponent. Yin-Yang theory also determines Tai Chi fighting strategy and has led to thirteen concepts [Jings] which guide practice and fighting. Thus, Tai Chi Chuan is also called "Thirteen Postures." Chang San-Feng Tai Chi Chuan treatise states "What are the thirteen postures? Peng (Wardoff), Lu (Rollback), Ghi (Press), An (Push), Chai (Pluck), Lie (Split), Zou (Elbow-Stroke), Kau (Shoulder-Stroke), these are the Eight Trigrams. Jinn Bu (Forward), Twe Bu (Backward), Dsao Gu (Beware of the Left), Yu Pan (Look to the Right), Dsung Dien (Central EQuilibrium), these are the Five Elements. Wardoff, Rollback, Press, and Push are Chyan (Heaven), Kuen (Earth), Kann (Water), and Lii (Fire) are the four main sides. Pluck, Split, Elbow-Stroke, and Shoulder-Stroke are Shiunn (Wind), Jenn (Thunder), Duey (Lake), and Genn (Mountain), the four diagonal corners. Forward, Backward, Beware of the Left, Look to the Right and Central Equilibrium are Gin (Metal), Moo (Wood), Sui (Water), For (Fire), and Tu (Earth). All together they are thirteen postures."

The eight postures are the eight basic fighting moves of the art, and can be assigned directions according to where the opponents force is moved. Wardoff rebounds the opponent back in the direction from which he came from. Rollback leads him further that he intended to go in the direction he was attacking. Split and Shoulder-Stroke lead him forward and deflect him slightly sideward. Pluck and Elbow-Stroke can be done so as to catch the opponent just as he is starting forward, and strike or unbalance him diagonally to his rear. Push and Press deflect the opponent and attack at right angles to his motion. The five directions refer to stance, footwork, and fighting strategy. They concern the way one moves around in response to the opponent's attack, and how one sets up one's own attacks."

- Dr. Yang Jwing-Ming. Advanced Yang Style Tai Chi Chuan. Volume One: Tai Chi Theory and Tai Chi Jing. By Dr. Yang, Jwing-Ming. Boston, Massachusetts, Yang's Martial Arts Academy, YMAA, 1986. Glossary, 276 pages. ISBN: Unknown. This book includes a detailed explanation of the concepts of Jing, Yi, and Chi; and an outstanding discussion of the Jings (pp. 68-210) of Tai Chi Chuan. VSCL. Quotes from p. 9, and p. 253 (Appendix 13).

| Taijiquan Jings | Eight Trigrams and Five Elements |

| Wardoff (Peng) | Heaven (Chyan) |

| Rollback (Lu) | Earth (Kuen) |

| Press (Ghi) | Water (Kann) |

| Push (An) | Fire (Lii) |

| Pluck (Chai) | Wind (Shiunn) |

| Split (Lie) | Thunder (Jenn) |

| Elbow-Stroke (Zou) | Lake (Duey) |

| Shoulder-Stroke (Kau) | Mountain (Genn) |

| Forward (Jinn Bu) | Metal (Gin) |

| Backward (Twe Bu) | Wood (Moo) |

| Left (Sou Gu) | Water (Sui) |

| Right (Yu Pan) | Fire (For) |

| Center (Sung Dien) | Earth (Tu) |

"Taiji Thirteen Postures is also commonly known as bamen wubu. Bamen translates as "Eight Doors" or "Eight Gates." Wubu means "Five Steps." Bamen is the theory of bagua (Eight Trigrams) in taijiquan It refers to the eight positions of bagua. Both taiji and bagua are Taoist philosophical theories. They are cosmological perspectives that provide a framwork for many Chinese, traditions such as traditional medicine, fortune telling and feng shui. The martial arts of taiji and bagua are based upon this theory too. Bamen consists of four straight directions, called sizheng, and four diagonal directions or four corners, called siyu. Si means four. Zheng means upright, straight, correct, main, chief and positive. Yu means corner or diagonal. According to Taijiquan Treatise by Zhang Sanfeng (believed to have created taijiquan in the Song Dynasty), the four straight directions are peng (ward-off), lu (roll-back), ji (press or squeeze) and an (press or push). In Eight Trigrams theory, these four straight directions correspond to four of the trigrams: qian (heaven), kun (earth), kan (water) and li (fire) respectively. The four diagonal directions are cai (pluck), lie (split), zhou (elbow-strike) and kao (body-strike or bump). They correspond to the trigrams of xun (wind), zhen (thunder), dui (lake) and gen (mountain). Furthermore, peng, lu, ji, an, cai, lie, zhou and kao are referred to as bafa (Eight Methods), as they represent eight different kinds of fighting techniques. These eight fighting techniques equate to eight kinds of jin (power manifestation) patterns that correspond the eight positions of bagua.

Wubu refers to the five skills revolving around

footwork. Wu means five. Bu means step. The Five Steps corresponds

to wuxing (five elements). In reference to Zhang Sanfeng's Taijiquan

Treatise, the five steps are qianjin (advancing), houtui

(retreating), zuogu (look to the left), youpan (glance the right)

and zhongding (central settling). The words "look" and "glance" in "look

to the left" and "glance he right" are merely metaphors used to describe

leftward and righnward actions with footwork and body movements. In five

elements theory, they correspond to jin (metal), mu (wood),

shui (water), huo (fire) and tu (earth) respectively. These

five footwork skills train the body to move in the most flexible way during

fighting."

- Taiji

Thirteen Postures, Master Shouyu Liang

Song of the Thirteen Postures

"The thirteen postures should not be taken

lightly;

The source of the postures lies in the waist.

Be mindful of the insubstantial and substantial changes;

The ch'i (breath) spreads throughout without hindrance.

Being still, when attacked by the opponent, be tranquil and move in

stillness;

(My) changes caused by the opponent fill him with wonder.

Study the function of each posture carefully and with deliberation;

To achieve the goal is very easy.

Pay attention to the waist at all times;

Completely relax the abdomen and the ch'i (breath) rises up.

When the coccyx is straight, the shen (spirit)

goes through the headtop.

To make the whole body light and agile suspend

the headtop.

Carefully study.

Extension and contraction, opening and closing,

should be natural.

To enter the door and be shown the way, you must

be orally taught.

The practice is uninterrupted, and the technique (achieved) by self

study.

Speaking of the body and its function, what is

the standard?

The i (mind) and ch'i (breath) are king, and the

bones and muscles are the court.

Think over carefully what the final purpose is:

to lengthen life and maintain youth.

The song consists of 140 characters;

Each character is true and the meaning is complete.

If you do not study in this manner, then you'll

waste your time and sigh."

-

Translated by Benjamin Pang Jeng Lo, Martin Inn,

Robert Amacker and Susan Foe

Charts for the Thirteen Gates:

Thirteen Tai Chi Chuan Postures, Movements, Stances, Techniques, and Powers

Charts

Terms and Translations Chart

| Gate/Technique |

Romanization and Term Variants |

1. Ward Off |

Peng, Pang; "bung" |

2. Roll Back |

Lu, Lei;; "loo" |

| 3. Press | Ji, C'hi, Qi, Jai; "chee" |

| 4. Push | An, On; "ahnn" |

| 5. Pull Down | Tsai, Cai, Tsai, Chai; "sigh" |

6. Split |

Lieh, Lie; "leeaay" |

7. Elbow |

Chou, Zhou, Jau; |

| 8. Shoulder | Kao, Kau; "cow" |

| Jin, Jin Bu, Chin Jeun, Qian Jin | |

10. Retreating Step |

Tui, Tui Bu, Hau Teui, Hou Tui |

| 11. Gazing Right, Stepping to the Left | Ku, Zou Gu, Jo Gu, Zuo Gu |

| 12. Gazing Left, Stepping to the Right | Pan, You Pan, Yau Paan |

| 13. Settling to the Center | Ding, Zhong Ding, Jung Ding |

Ba Fa Chart

These attributions are based on a variety of readings and interpretaions:

| Gate/Technique | Trigram - I Ching | Direction | Element | Body |

| Heaven, Sky, Chien | Southeast | Heaven | Head, Arms | |

| Earth, Kun | Northeast | Earth | Dan Tien, Sex, Hips, Legs | |

| 3. Press - Ji | Water, Kan | South | Water | Kidneys |

| 4. Push - An | Fire, Li | North | Fire | Heart, Blood |

| 5. Pull Down - Tsai | Wind, Sun | Northwest | Wind | Spleen, Gallbladder |

6. Split - Lieh |

Thunder, Chen | West | Thunder | Liver, Pancreas |

7. Elbow - Chou |

Lake, Tui | East | Lake | Lungs, Blood |

| 8. Shoulder - Kao | Mountain, Ken | Southwest | Mountain | Stomach, Intestine |

| Metal | ||||

| Wood | ||||

| 11. Stepping to the Left - Ku | Water | |||

| 12. Stepping to the Right - Pan | Fire | |||

| 13. Staying Centered - Ding | Earth | |||

Different Associations of Eight Gates to Eight Trigrams:

Yang Ch'eng-Fu, 1931, in Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions, pp. 130-138

Ward-Off (Peng), South, K'an

Roll-back (Lu), West, Li

Press (Ji), East, Tui

Push (An), North, Chen

Pull-Down (Tsai or Cai), Northwest, Hsun

Split (Lieh), Southeast, Ch'ien

Elbow-Stroke (Chou), Northeast, K'un

Shoulder-Stroke (Kao), Southwest, Ken

Zhang Yun, Taiji Thirteen Postures.

Ward-Off (Peng), North, Kuan, Water

Roll-Back (Lu), South, Li, Fire

Press (Ji), East, Zhen

Push (An), West, Dui

Pull-Down (Tsai or Cai), Northwest, Qian

Split (Lieh or Lie), Southwest, Kun

Elbow-Stroke (Chou or Zhou), Northeast, Gen

Shoulder-Stroke (Kao), Southeast, Xun

Jou, Tsung Hwa, The Tao of T'ai-Chi Ch'uan: Way to Rejuvenation, 1980.

Ward-Off (Peng), South, Chien, Heaven

Roll-Back (Lu), North, Kun, Earth

Press (Ji), West, Kan, Water

Push (An), East, Li, Fire

Pull-Down (Tsai or Cai), Southwest, Sun, Wind

Split (Lieh or Lie), Northeast, Chen, Thunder

Elbow-Stroke (Chou or Zhou), Southeast, Tui, Lake

Shoulder-Stroke (Kao), Northwest, Ken, Mountain

Stuart Alve Loson,

T'ai

Chi According to the I Ching, 2001

From the classic text: "The Eight Gates and Five

Steps Discourse," p. 76-83

Ward-Off (Peng), Southeast, Chien, Heaven

Roll-Back (Lu), Northeast, Kun, Earth

Press (Ji), South, Kan, Water

Push (An), North, Li, Fire

Pull-Down (Tsai or Cai), Northwest, Sun, Wind

Split (Lieh or Lie), West, Chen, Thunder

Elbow-Stroke (Chou or Zhou), East, Tui, Valley

Shoulder-Stroke (Kao), Southwest, Ken, Mountain

Sifu Kent Mark, The History of Tai Chi Chuan

Ward-Off (Peng), South, Chien, Heaven

Roll-Back (Lu), North, Kun, Earth

Press (Ji), West, Kan, Water

Push (An), East, Li, Fire

Pull-Down (Tsai or Cai), Southwest, Sun, Wind

Split (Lieh or Lie), Northeast, Chen, Thunder

Elbow-Stroke (Chou or Zhou), Southeast, Tui, Lake

Shoulder-Stroke (Kao), Northwest, Ken, Mountain

8 Gates, 8 Elements, 8 Postures, 8 Jings, 8

Ways, 8 Stances

Eight Gates, Eight Elements, Eight Postures, Eight Jings, Eight Ways, Eight

Stances, Eight Energies

13 Postures, 13 Gates, 13 Elements, 13 Jings, 13 Ways, 13 Stances. 13 Tactics

13 Kinetic Movements, 13 Basic Taiji Quan Skills

Thirteen Postures, Thirteen Gates, Thirteen Elements, Thirteen Energies,

Thirteen Ways, Thirteen Stances

5 Directions, 5 Movements, 5 Steps, 5 Stepping Movements

Five Directions, Five Steps, Five Movements, Five Stepping Movements

Tai Chi Chuan, Taijiquan, T'ai Chi Ch'uan,

Tai Chi, Tai Ji Quan, Taiji, Tai Ji Chuan, Tie Jee Chewan

Chi Kung, Qi Gong, Qigong, Chee Gung, Qi, Chi, Tu Na, Dao Yin, Yi, Neigong, Kung

Fu

Internal Martial Arts, Soft Style Martial Arts

© Michael P. Garofalo, 2004-2021, All Rights Reserved

This webpage work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License,

© 2004-2021 CCA 4.0

Created and revised by Michael P. Garofalo,

Green

Way Research, Valley Spirit

Center, Gushen Grove Notebooks, Red Bluff, North Sacramento Valley, California,

USA (2010-2017)

Revised and updated by Mike Garofalo,

Green Way Research, Cloud Hands Home, City

of Vancouver, State of Washington, Northwestern USA, (2017-)

This webpage was first posted on the Internet on April 15, 2004.

This webpage was edited, improved, changed, modified or updated on May 3, 2021.

Brief Biography of Michael P. Garofalo, M.S.

Cloud Hands: Tai Chi Chuan and Chi Kung Website